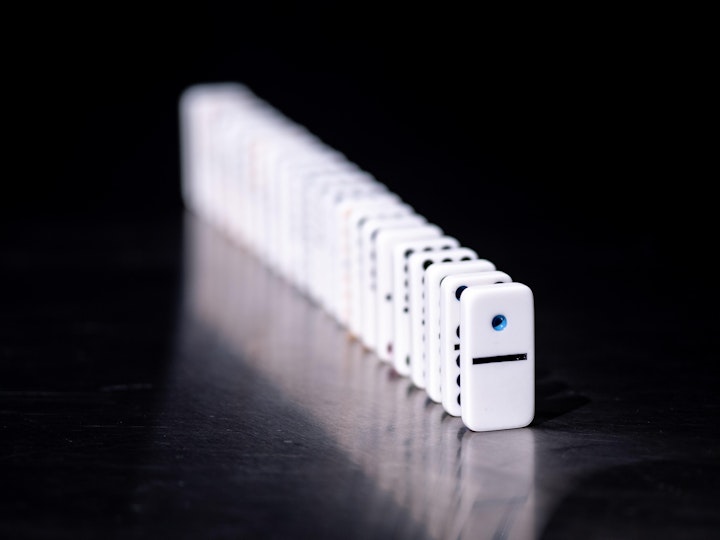

The domino effect: what do rising interest rates mean?

Rising interest rates makes a company's debt more expensive - but what does this mean for the economy? Dr Nikolaos Antypas explains in for Leading Insights.

The Bank of England has announced a generally expected rise of the benchmark interest rate to 1%, just 0.25% higher than the previously prevalent rate, putting interest rates at the highest level since the time of the Global Finance Crisis in 2009. The rise seems insignificant in absolute size, but the economic environment seems vulnerable to even minute changes in monetary or fiscal policy.

Western countries, including the UK, are used to "cheap" capital, primarily debt. Mortgages, debt-funded capital expenditure, and business acquisitions have been on an upward trend for the better part of the last decade on the back of inexpensive capital, which could presumably be paid off relatively easily with even modest growth in output. The rise in interest rates means that, along with the inflation-led slowdown in growth, the inexpensive debt will have to be rolled over to more expensive debt in an environment of economic slowdown or contraction. This puts a significant proportion of companies at risk of not being able to pay their debts.

The inability of a few companies to repay debt, and the downsizing that it entails, can have a domino effect on other businesses, which have been otherwise less levered and in better financial health. For instance, if a client firm becomes insolvent and stops buying services from a financially healthy vendor, then the vendor may have to downsize so that it eliminates unnecessary operating capacity. This process can happen across the economy, leading to lower employment. This leads to lower consumption, and subsequently, less business activity: the vicious circle of a recession can accelerate fast, and any state support will come at a steep cost for future generations.

The UK, EU, and North America have shown great resilience in the last couple tumultuous years. This, however, may have been achieved by depleting the monetary policy arsenal. The ongoing war in Ukraine and the related strains in supply chains and energy prices have only accelerated a trend towards a correction. It will only remain to see whether the Bank of England, and other central banks, can achieve the broadly coveted "soft landing".

You might also like

The future of work - hybrid

Return to work means focus on creativity, collaboration and caring - and AI

Is staycation inflation here for good?

This site uses cookies to improve your user experience. By using this site you agree to these cookies being set. You can read more about what cookies we use here. If you do not wish to accept cookies from this site please either disable cookies or refrain from using the site.